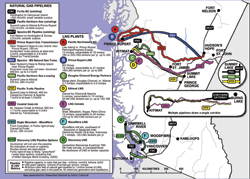

BC Premier Christy Clark and that Energizer Bunny® resource salesman we call Prime Minister have been making a lot of noise lately about Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) sales to Asian markets. Clark once claimed BC LNG would be the cleanest in the world, although lately she has been defining her terms and now says only the actual LNG facility, not the gas or the pipelines, will be super natural green. (Click on map to enlarge)

BC Premier Christy Clark and that Energizer Bunny® resource salesman we call Prime Minister have been making a lot of noise lately about Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) sales to Asian markets. Clark once claimed BC LNG would be the cleanest in the world, although lately she has been defining her terms and now says only the actual LNG facility, not the gas or the pipelines, will be super natural green. (Click on map to enlarge)

BC’s Energy Objectives Regulation requires that “93% of the electricity generated in BC must come from clean or renewable resources.” Last year Clark’s government decreed that electricity generated from natural gas “to serve demand from facilities that liquefy natural gas for export by ship” would be excluded from the 93% requirement.

But a flip of the pen doesn’t begin to deal with the question. The stakes are high, there’s a lot of money at play, and there are a multitude of issues for the land, the water and the people.

Methane, Natural Gas & LNG

LNG is natural gas which has been cooled to about minus 162°C, where it becomes a liquid, and takes up only 1/600th of the volume it requires as a gas. As a liquid, it can be transported in special tankers.

Natural gas is mostly made up of the gas methane, CH4 – one carbon atom and four hydrogen – a simple fossil fuel. Like all fossil fuels, it emits carbon dioxide when it is burned, though methane is often presented as the “cleanest” of the fossil fuels. There is, however, a catastrophic Hyde to methane’s clean Jekyll: because it is such a small molecule, invisible and odourless, methane leaks constantly and from everything when it is handled, and these “fugitive emissions” are estimated to run as high as 6% or more of the natural gas produced.

Methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide – and an immediate effort to stop releasing unburned methane would pay off in combating climate change faster than any other effort. However, methane is created by nature whenever carbon-based substances rot in the absence of oxygen – in landfills, flooded areas, dying forests, cows’ digestion, sewage.

Air pollution

Although it is considered a clean fuel, when burned, natural gas emits very fine particulate, which has no safe limit for human health, because of impacts to the lungs, and the heart.

Greenhouse Gas

The production of shale gas releases methane all along the way, from the well heads through the processing plants, through the pipelines, and into our homes, factories, mills where it is burned, and LNG plants where it is liquefied. By some estimates, these methane leaks make natural gas as bad for climate change as coal.

Fractured Landscape

Because shale gas is not contained in pools, like conventional gas, but is trapped in the shale somewhat like water in a sponge and must be fractured out, hundreds and thousands of wells are required are required for mass production, along with roads and pipelines, creating massive disturbance of the natural landscape. In particular, the Valhalla Wilderness Society is warning that the planned pipeline that would feed the Petronas project runs through protected areas adjacent to the Khutzeymateen Grizzly Bear Sanctuary.

Water

In 2012, according to the BC Oil & Gas Commission (OGC), the oil and gas industry in BC used 3.8 million cubic metres (m3) of water from short-term water licenses, defined as less than one year, (18.5 per cent of the approved volume), comparable to the 2011 volume of 3.7 million m3.

But in 2012, a total of 7.1 million m3 of water was used just for hydraulic fracturing of about 9,000 wells (this total includes short term permits as well as long term leases). The greatest average water use was 76,923 m3 per well in 50 wells in the Horn River Basin.

The OGC says that in 2012, the maximum surface water usage was less than 0.075% of the mean annual runoff in the northeast watersheds. In the same year, industry produced 1.45 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas (CAPP Statistical Handbook, 2012 Data).

Supply of Natural Gas

As of 2013, the National Energy Board reports that it has approved three export permits, totalling 1.7 trillion cubic feet per year (Douglas Channel Energy, Kitimat LNG and LNGCanada) and five more are pending for 4 trillion cubic feet per year (Pacific Northwest, BG Group, Woodfibre, WCC LNG [Exxon] and Jordan Cove) – for a total of 5.7 tcf/year. However, in 2011, the most recent report available to the public, the BC Oil and Gas Commission estimated natural gas reserves at 34.6 tcf.

That would supply roughly six years of production for current export licences, not the 80 years touted by the BC government (“BC LNG: Shale gas expert David Hughes debunks minister’s math,” Common Sense Canadian, September 2013)

Energy

Cooling natural gas to a liquid takes enormous energy, mainly for the refrigeration compressors, and amounts to about 85% of the electricity demand of a LNG plant. BC Hydro says that if it supplies only the other 15%, the non-liquefaction load, it will have enough surplus capacity to meet 3,000 gigawatt hours (GWh) of demand from LNG plants to 2021 – less than half its upper estimate for potential demand from LNG plants.

The upstream activities with natural gas – producing and processing it – also take a lot of energy. So will transporting it across the province to the coast from the Horn River and Montney basins in the interior. BC Hydro states that it is not planning to provide power for hydraulic fracturing or for pipeline compression – gas or diesel will provide the former power, and natural gas the latter.

Hydro’s planning also includes building Site C, the third hydroelectric dam on the Peace River, to provide an extra 5100 GWh by 2024 (BC Hydro Integrated Resource Plan, August 2013.) BC Hydro does not link Site C to Horn River, but former Energy Minister and now Senator Richard Neufeld has done so – stating that the gas play demand is in the order of 500 Mw, “a significant amount of Site C.” (“Senator wants Site C dam to power fossil fuel extraction, environmentalist charges,” Matthew Burrows, Georgia Straight, February 11, 2010)

Markets

Because the United States has been busily exploiting its own shale gas, it does not expect to import much gas from BC. North America is awash in this boom of fracked shale gas.

That’s why the big buzz, the pot of gold, is now in Asian markets for LNG, such as Japan where the current price is $16 as opposed to under $5 in North America. That price differential is producing potential investment announcements every other day, the most recent being an eye-popping offer to invest $36 billion in BC from Malaysia’s government-owned Petronas, owner of the Pacific Northwest LNG project.

Notably, none of the financial buzz and big promises have so far been accompanied by any firm commitments by the companies. That is because those companies who might invest in LNG are playing one jurisdiction off against another, increasingly dealing for the lowest costs and highest subsidies where the natural gas is produced.

Premier Clark would have us believe that opening the taps on LNG will simultaneously open a flow of cash into BC.

Chevron’s Jeff Lehrmann, Apache’s partner in Kitimat LNG, says that’s not going to happen: “Big uncertainty surrounds what fiscal regime the project will face in British Columbia,” (“Kitimat LNG project’s fate depends on numbers,” Dan Healing, Calgary Herald, October 16, 2013).

The BC government is promising royalty rates which they claim will simultaneously be pleasing to industry and taxpayers. You judge: natural gas is already a giveaway in BC with an effective royalty rate in 2012/13 of 6.9%. It’s not difficult to see that this might be pleasing to industry, but impossible to understand why BC citizens should find it acceptable.

BC’s powerful First Nations remain cautiously interested in partnering in this resource development because it is seen as less damaging than oil, while still offering badly needed revenues and jobs to their communities. However, Lehrmann “is also looking at bringing in foreign temporary workers.”

Fracking

Hydraulic fracturing – fracking – is almost universally used in shale and tight gas wells to maximize the gas production from those wells. It is often a near-continuous process along the length of a well.

Sand and a wide variety of unregulated and undisclosed chemicals are pumped into the shale and the tight formations to open them up (fracture) and release the natural gas. Some of the chemicals used in fracking are long- lasting toxics, which would otherwise be hazardous waste, and have contaminated aquifers. Other toxics which have been trapped in the rock, such as sulphides, arsenic, and even radioactivity can be released in the process. Fracking over large areas is also proven to cause localized earthquakes.

The environmental risks and impacts of fracking are well documented, and opposition to fracking projects now precedes the activity. Communities around the world – because shale gas potential appears to be just about everywhere – know about it, and object. In part, this is because the shales underlie many densely settled areas, and the work takes place in the water people drink and on the edge of their properties. In North America, fracking the Marcellus Shale, which runs from New York through Pennsylvania, West Virginia and into Tennessee, and the Barnett Shale in Texas are good examples. In October, violence flared, police vehicles were burned, and many were arrested at a First Nations blockade in New Brunswick. Quebec, the only jurisdiction in Canada which has officially put a stop to fracking, is being sued under NAFTA by the company using the technique under the St. Lawrence River.

In BC, the proliferation of drilling and fracking is in remote areas. Few humans may be affected, but water is, and extensive land is compromised. Government’s cynical response to concerns about fracking is in sections of the 2010 Oil and Gas Activities Act and a 2013 change to the Water Act which extended already widely criticized and overused “short term” permits from one year to two.” In 2012, West Coast Environmental Law acknowledged the great progress that was being made with this headline in its blog: “BC Oil & Gas Commission hires a hydrologist – about time!”

Champions of the regulatory regime will point at some of the stronger language in the Oil and Gas Activities Act. The problems are: that most of the reporting is done by the companies themselves; the OGC has almost no staff to monitor what’s really going on; the OGC questionable motivation to catch or prosecute offenders; and virtually all of the activities of concern are miles in the bush and deep underground. Monitor that!

***

By Delores Broten with thanks to Arthur Caldicott, the Northwest Institute for Bioregional Research, Smithers, and the Skeena Watershed Conservation Coalition, Hazelton, BC.

Sources: Watershed Sentinel files, and Fracking by the Numbers: Key Impacts of Dirty Drilling at the State and National Level, John Rumpler, Environment America Research & Policy Center, October 2013; “About LNG,” Northwest Institute, Smithers BC, revised October 2013; Water Use in Oil and Gas Activities, annual reports, BC Oil & Gas Commission; Methane Emissions from Natural Gas Systems, Howarth et al, 2012, http://www.eeb.cornell.edu/howarth/publications/Howarth_et_al_2012_National_Climate_Assessment.pdf

*Like what you read? Support independent media and take advantage of our 2014 Wildlife Calendar special*